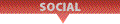

K-25 was the medium I chose to handle the extreme enlargement required for this home builder’s model center. An 11"x14" interneg was used for the enlargement.

Unique Medium Stretched the Boundaries of Possible

December, 2010 | by John Siebenthaler | photo©john siebenthaler

(NEW PORT RICHEY, FL) There was a time, in the ’70s, when Very Large Pictures Of Otherwise Ordinary Things didn’t just happen over the weekend. Before wide format inkjet printing, upsampling, ftp, media cards, and an app for that, photographers worked with interior designers and photo labs to wring expensive impact out of specially formulated display film or, less frequently, standard enlarging paper.

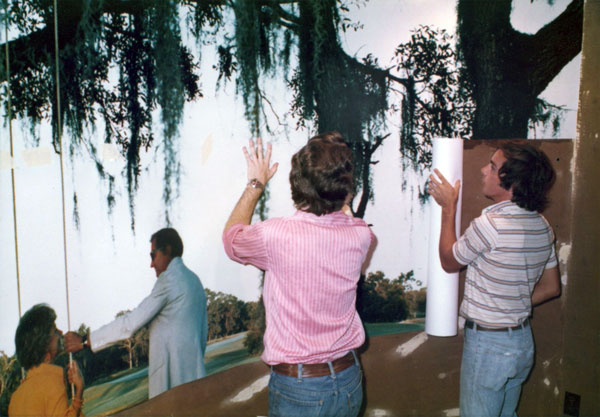

In 1974 it took two lab techs from Meisel’s commercial Atlanta lab two days to hang the three-section mural on the specially prepared panoramic wall, the culmination of several months of assignment prep, lab work and media design and construction.

As it turned out, the image would be the largest print installed up to that time in the southeast, larger even than the displays at Disneyworld.

When finished, the welcome center featured several dozen images of various sizes, most of which were devoted to picturing the wildlife and heritage of the region, along with the requisite commercial interiors and exteriors. Never thought to figure out how many snapshots it would have equaled.

for more information on large graphics contact siebenthaler creative

On December 30, 2010, when the very last lab to still process Kodachrome — Dwayne’s Photo Service of Parsons, Kansas — runs the last roll of Kodachrome to ever be processed — they already ran the last roll actually produced by Kodak earlier this year — perhaps the single most important chapter in analog color photography will end.

As a commercial and editorial photographer for roughly two and a half decades, from the ’70s into the ’90s, this is my story of the largest photo I ever shot.

It was a collaborative effort between the Clearwater, Florida design department of what was then the biggest home builder in the country, U.S. Home, one of the largest commercial photo labs in the country, Meisel, and one tiny frame of iconic K25 (as it had come to be labeled), selected by me as the film choice for the assignment on the basis of its legendary grain, gamma and saturation. And because I wanted to see if it would work.

The concept of a nostalgia-themed welcome center for a golf course community in west central Florida came from Dennis Eckle, then marketing director for custom home builder Rutenburg Homes. His department was responsible for designing the center, and he was receptive to my pitch for using an oversized, wall mounted photomural as the main focus.

At the time, photomurals were just reaching fad status and briefly fed the new market for stock commercial images that split off from the traditional editorial channel. Commercial developers throughout the country, from malls to banks to shopping centers, were clamoring for really big prints of tree bark, gurgling streams, and bees on flowers that could be hung just about anywhere.

Enlarged 12,000% — The Largest of Its Time

I’d never even seen a print of the size proposed. I’d printed my own 16X20-inch b&ws, had ordered 20x24-inch portraits, and some of my color stock was sold as larger format wall prints, but this was unfamiliar territory on a grand scale.

The lab techs at Meisel in Atlanta thought it would work, although they weren’t aware of anyone having tackled a theme this large from sheet film, let alone 35mm film.

Try this out for detail: standing in front of the mural, you could tell the time on the male model’s wristwatch, which on the original K25 slide is smaller than the head of a pin.

As it turned out, the image would be the largest print installed up to that time in the southeast, larger even than the displays at Disneyworld. The project would require a custom built curved Masonite wall for mounting. Two lab techs to install. And a critical 11x14-inch interneg from a 7/8 by 1-3/8-inch piece of positive slide film to handle the 12,000% scaling needed to project the image onto three strips of color print paper to produce the eight-foot high, 14-foot wide mural.

Preparing For An Eight-Foot Tall Analog Enlargement

Models were selected, a golf course location overlooking a fairway was chosen, and I loaded a tripod-mounted Leica SLR with K25, praying for good weather and a result I could point to in front of my sheet-film peers and say, "See, I told you so!"

I had Kodak, in Rochester, run the film, before shipping to Meisel for the interneg and sectional print. When that was finished, two lab techs delivered the project to the site. It took two days to hang, using dry mount adhesive and very careful use of a dry mount tacking iron to secure the print to the wall’s surface.

How good was it? Try this out for detail: standing in front of the mural, you could tell the time on the male model’s wristwatch, which on the original K25 slide is smaller than the head of a pin.

Some years later, and after famously — and fearlessly — predicting in the early ’00s that digital photography was interesting but would never unseat conventional analog imaging, I use trusty, and very utilitarian, point and shoots. Instant gratification, video on demand, choice of programs. And none of the anxiety, or excitement, of having to wait days for the results.

That’s my Kodachrome story. Nice bright colors and all.